My Father’s African Heart

MY FATHER’S AFRICAN HEART

By Adriana Marchione

As I write this, I am flying back to the West Coast after a trip to help my family bury my father’s ashes in a green burial site next to Holy Cross Abbey in Berryville, Virginia. The cemetery, run by Cistercian monks, is in a beautiful setting surrounded by the Shenandoah Mountains. My father was born into a Roman Catholic family in Torrington, Connecticut, and remained a devout Catholic throughout his life. Ever since he was a young man, he always tried to have an ongoing relationship with a spiritual advisor, and in later years he began meditating, reading contemplative literature and going on retreat at the Abbey where he would take counsel from Father Joseph, a monk from South Africa. Father Joseph conducted the simple service for my father, and stated that it felt remarkable to be a part of this final resting ceremony for my dad after all their time spent together talking about God.

As could be expected from such an event, I am filled with remembrance, nostalgia and a strong feeling of connection to my Italian-American father, Thomas Marchione. He grew up with distinct Italian influences: Italian food, the language of my great-grandparents and their ancestors, and the love of Italian culture. My father had that typical Italian temperament which came through in his passion for life, his use of hand gestures, a deeply affectionate nature and an often demanding and headstrong way of communicating. I have been reflecting on the ways my father influenced me and inspired me, most notably through his international work as an anthropologist.

My father’s life was committed to service, especially as an advocate for the poor, hungry and malnourished. His career as a medical anthropologist brought him around the world, allowing him to help many people through his writing, teaching, grassroots work and eventually the initiatives he championed while working at the United States Agency for International Development. Although he traveled to many countries, his love of Africa always shone through for me; it felt like a pulse that was a part of his soul’s calling. My parents met in Liberia, West Africa, where they were Peace Corps volunteers in the 1960s. They both taught at a Methodist mission school, my father physics and chemistry and my mother English and geography. It was a time of great discovery for both of them, which marked their initial bond with each other, and a meeting of many friends who wove into the fabric of our lives over the years.

Our house was filled with African art and objects, such as letter openers, musical instruments, wall hangings and masks. Every time my father made a trip to Africa he brought something home with him that took a prominent place in the house. He wore African shirts decorated with colorful patterns, my favorite being one with beer bottles on it that I wore when I got older, feeling rebellious in my father’s clothes. His trips to Malawi, Tanzania, Ghana, Ethiopia, among other African countries, were so fascinating to me (they were also interspersed with travels to Sri Lanka, Guatemala and other developing nations.) After long stretches of time away from home, he would come back looking very alive, bearing gifts and embodying a certain ease and joy. I felt that he was imbued with something special that fed his heart, and I sensed a freedom surrounding him.

We knew many Africans through church and the university community in Cleveland, Ohio, where I grew up. There was a particular couple I remember who would come over for dinner. They dressed and spoke English differently and I was struck by their kindness and the warmth between them and my parents. We also lived in Jamaica when I was very young (between the years of 2-6) where my father worked on health and nutrition issues at the Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute and then conducted his Ph.D. research, an evaluation of a community health aide program. This time in the Caribbean also shaped me. My parents listened to Bob Marley and Jimmy Cliff and my best friend was a young Jamaican girl named Cheryl, with whom I still am in contact through Facebook no less! I have fond memories of swimming in the ocean, playing dress up outside with Cheryl and other friends, as well as vague remembrances of what to me were extreme experiences – for example watching a chicken get its head cut off while sneaking around back alleys.

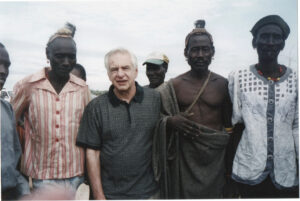

Though Africa is a place I never visited, the memories of my father’s trips are still very vivid to me. There was fear and uncertainty as he would fly off on his own to encounter the heat, the povertyand the long travel to drop himself into a world so unlike his own. I have a distinct recollection of my father calling from a hotel and describing the beauty of the place. I imagined palm trees, stone floors, and windows with a breeze coming in to fend off the heat. He would eat spicy food, goat meat, lots of rice and beans and loved the fare – even though it often upset his stomach. I imagine there was an immediacy about life for him there. He would share pictures with us of the villages, the children, the people he worked with, and the conditions that shaped day to day life.

My work is also about service. I am gifted to work in arts and movement education. I teach an international body of students who visit California from Europe, Latin America, Australia and Asian countries. In addition many students with diverse backgrounds come to the Tamalpa Institute where I teach. It is so familiar and comfortable to be among them, having been brought up as part of a global community. Even though people see me as ‘white’ I know that my soul has many colors born out of Italian roots, my mother’s Belgian and Scandinavian background and the mysterious beat of a African heart that still signals my father’s desire towards service and connection to something that nourished him in ways I will never quite grasp. As he got older, the trips to Africa and other countries became less frequent. Yet when he died, I sensed that Africa still lived in the background. Before the heart attack that took my father’s life, my parents were considering going back to the Peace Corps upon retirement. I often wonder if Africa was calling him again.

Adriana Marchione is an arts and movement educator/therapist and a filmmaker. She is well-versed in helping people use the arts to recover from difficult life issues including addiction, trauma and grief. She has recently released her film, ‘When the Fall Comes’ which shares her personal story exploring love, loss and art inspired by the loss of her husband and father. On January 23 and 24, 2016 she will offer a grief and arts workshop with co-facilitator and musician Steve Podry at the Joe Goode Annex in San Francisco. Find her at www.adrianamarchione.com and whenthefallcomes.com

Self-Published, November 2015